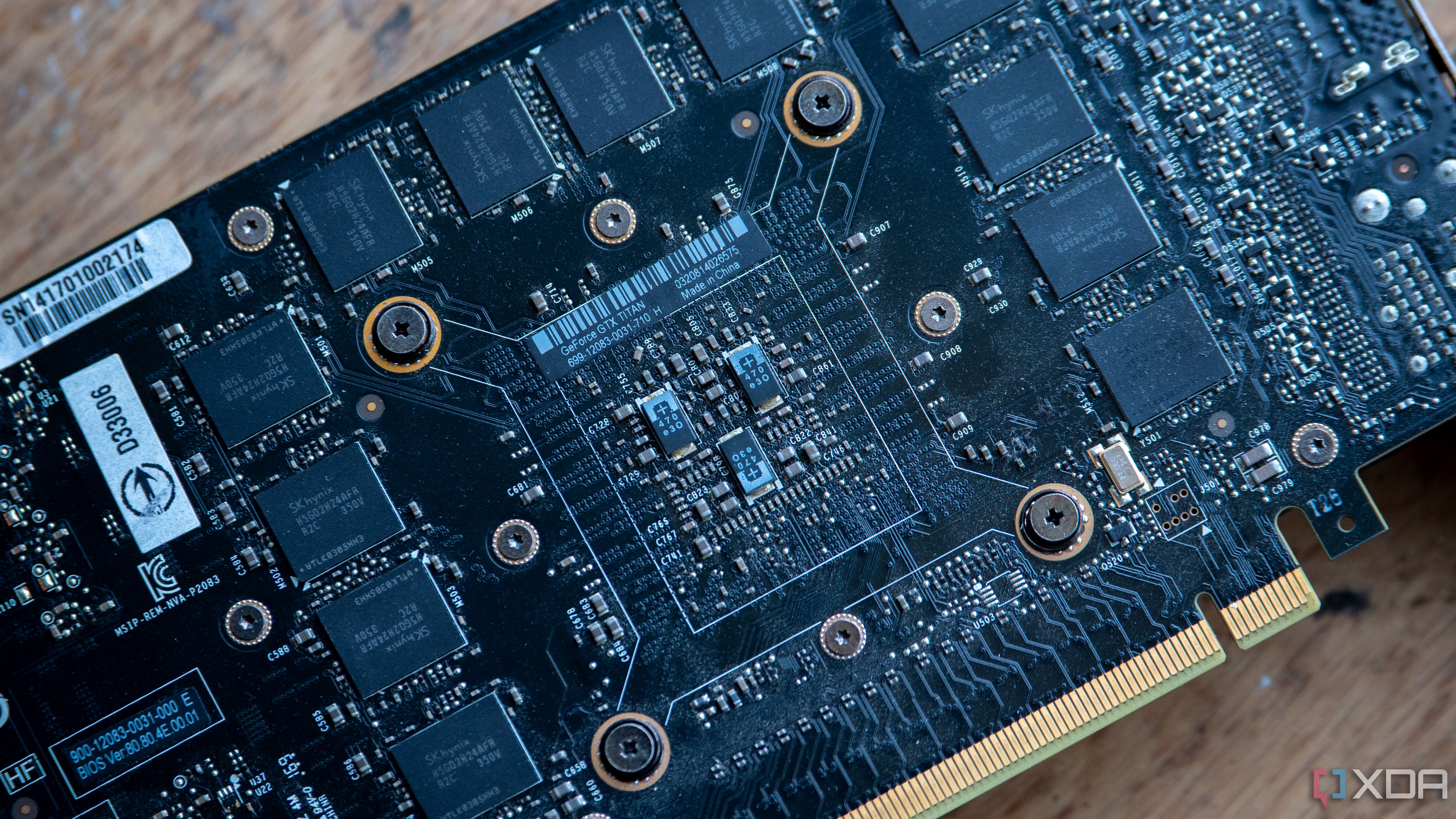

Think back to 2013, a year where we saw some amazing big titles launch, such as Battlefield 4, Metro: Last Light, and Grand Theft Auto V. Some of these were tough to run at maximum settings, but there was an answer: Nvidia's GeForce GTX Titan. It packed seven billion transistors, 6GB of GDDR5 VRAM, and drew, what was considered at the time, a pretty high 250W to run. There were no RT or Tensor cores either; just 2,668 regular GPU cores, and it supported SLI too.

This kind of card didn't come cheap, and it was reserved for enthusiast-level gamers with its commanding price tag of $1,000... a price that would excite PC gamers for a Titan-class GPU today. Nvidia demoed it in a three-way SLI running Crysis 3 at a 5760x1080 across three monitors, giving gamers a GPU that could "power the world's first gaming supercomputers."

This GPU was truly a behemoth in every sense of the word, and I remember looking in awe at the incredibly powerful builds that people put together, running multiples of them in SLI to test the most intensive games. At the time, I had a mere GTX 560 Ti, upgrading to an AMD Radeon R9 270X the following year. For my teenage self, the Titan seemed like an unattainable card because, in fairness, it was. Now, more than a decade later, I own one of these, and I took a trip down memory lane as a result.

The story of the Nvidia GeForce GTX Titan

A first of its kind for consumers

First and foremost, Nvidia's original Titan wasn’t born in a gaming lab at all... it escaped from a super-computer.

Back in late 2012, Oak Ridge National Laboratory switched on Titan, a Cray XK7 system that vaulted to the number one spot on the Top 500 list. Inside every one of its 18,688 nodes sat a Tesla K20X accelerator built on Nvidia's brand-new GK110 silicon. That 7.1-billion-transistor die was designed for scientific code, not Crysis: it was focused on double-precision floating point math and easily went through climate models, fusion simulations, and, increasingly, early deep-learning workloads. It was a true workhorse.

But when Nvidia's engineers saw how many gamers were flashing modified BIOS files onto workstation-class cards just to play games like Battlefield 3 faster, something clicked. What if they officially wrapped the same monster chip (more or less) in GeForce clothes? Thus, in February 2013, the GTX Titan arrived: essentially a Tesla K20X with some changes to reduce it to a $999 MSRP, which still felt like an out-of-this-world price when sitting next to the $499 GTX 680.

The other major advancement made by the Titan was its focus on capacity, not clocks. It packed six gigabytes of GDDR5 VRAM on a 384-bit bus, which sounded incredible next to the 2 GB limit of the GTX 680. It also solved a real bottleneck: open-world games and early high-resolution texture packs were already bumping into memory walls at the time. Combine that with 288 GB/s of bandwidth, and the card could stream massive geometry sets without completely thrashing PCIe. Running multiple in SLI, for gaming workloads, made it simply unbeatable.

However, there was one change here that could be credited with changing the entire trajectory of Nvidia as a company in the last decade. Even with its double-precision capabilities massively reduced to just a third when running at stock clocks, it still delivered an impressive 1.3 TFLOP/s of FP64. Its compute capabilities were completely left open to play with, a first for a consumer-class GPU. There was no other card in Nvidia's lineup that offered compute like this at the time to just anyone, and the equivalent AMD competitors based on Tahiti, such as the Radeon HD 7970, were still simply outclassed across the board.

There's one other change here that could be seen as the beginning of a terrible trend in GPU pricing. The Titan, with its ludicrous $1,000 price tag, was arguably a test to see if there was a market of enthusiasts, or "prosumers", that would spend way more than the typical GPU price of the time. This kicked off the trend of cards like the GTX 1080 Ti being priced at $699, the RTX 3090 being priced at $1,499, and the RTX 4090 being priced at $1,599. Every one of these cards arguably took a page out of Titan's book when it comes to pricing.

Titan legitimised the idea that a consumer GPU could stay relevant outside gaming for an entire decade. Home lab researchers can still use the card in refurbished workstations to prototype CUDA-accelerated code paths on the cheap; retro enthusiasts still love to play around with it and test out the high-end tech of a decade ago; and collectors prize its milled-aluminium shroud as the moment that PC hardware began to look like industrial equipment rather than tacky gaming devices. Even its limits tell a story: 6 GB of VRAM in a card of this calibre, relative to its time, is less than the bare minimum these days.

Related

Nvidia's RTX 5060 already feels out of date

DLSS is the only trick that the RTX 5060 has up its sleeve.

How does the GeForce GTX Titan fare today?

Not very well in most cases

The unfortunate truth is that my GTX Titan no longer works; the workstation PC that I was given with it started smoking once I booted it, and my personal computer entirely refuses to boot when I put the Titan in it, met only with a PSU click and nothing more. It's a protective mechanism of my power supply kicking in as it detects a short, so for all intents and purposes, the card is simply a paperweight. With that said, it's not exactly hard to tell how it would fare today; after all, practically every benchmark you can think of is public, and countless enthusiasts have revisited the card every couple of years to check in on how it's doing.

In nearly every way that you can pitch the Titan, it simply hasn't aged well. Practically every modern game will struggle to achieve 60 FPS and above, but where things didn't age as badly is when it comes to certain compute workloads, the most meaningful being its FP64 prowess. Measured at 1.3 TFLOP/s, it's still higher than the FP64 performance of the RTX 4050, which boasts just 211.2 GFLOP/s in comparison. On top of that, its memory bandwidth still surpasses the RTX 4050, offering 288GB/s compared to the 4050's 192GB/s.

Obviously, priorities change over time, and the RTX 4050 beats the original Titan in every other imaginable way aside from some very niche areas, but it's incredible just how much compute the original Titan had, even in comparison to today's entry-level cards. Nowadays, FP32 performance is significantly more important, and the RTX 4050 would handily beat the Titan in that realm, too.

The Titan isn't a museum piece these days because of its performance or what it can offer today. In most cases, it's not even worth the $50 you'll pay for one on the second-hand market. Instead, it's a testament to both how far we've come in GPU performance and the architectural changes that are now commonplace in today's GPUs. Unified drivers, large memory, and compute for everyone. That's what the Titan meant, and it was the first time gamers, homelabbers and researchers, and lovers of well-designed hardware all pointed at the same piece of silicon and said, "That's what I want."

.png)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·