In 1982, Atari tried to leap ahead with the 5200. It had better graphics, analog controls, and a redesigned cartridge slot that made it incompatible with the Atari 2600’s massive game library. That one change cost them. Players weren’t interested in starting over, and without support for older titles, the 5200 struggled to build momentum. Atari eventually released an adapter, but by then it was too late.

When the company came back in 1986 with the 7800, it didn’t make the same mistake. This time, compatibility wasn’t just included—it was advertised on the box. In the years that followed, console makers went back and forth—some building full support into the hardware, others cutting it without warning. But every time, it sent a message about whether players’ past investments still mattered.

Now, as Nintendo prepares to launch the Switch 2 on June 5, 2025, gamers are watching closely. The company has confirmed that the new console will support both physical and digital games from the original Switch, though not without exceptions. This history of backwards compatibility covers everything from the early days of including the same hardware as a console's predecessor, to adapters and digital emulation.

Related

5 Obscure Nintendo consoles you’ve likely never heard of

Nintendo’s history is full of experimental and regional-exclusive consoles. Here are five unique systems you might have missed.

Atari 7800 brings backwards compatibility

2600 hardware returns after the 5200’s failure

The Atari 7800 launched in 1986 with support for nearly every Atari 2600 game. That wasn’t common at the time, and marked the first backwards-compatible console. For older titles to work, the new console had to physically contain the same hardware as the original system. So Atari included the 2600’s TIA and RIOT chips inside the 7800, alongside its upgraded components and a new graphics chip called MARIA.

The design was a direct response to the failure of the 5200, which had dropped support for 2600 cartridges entirely. That version of “next-gen” didn’t land. Gamers rejected the idea of leaving their libraries behind, and the 5200’s small game selection didn’t help. Atari eventually released an adapter, but it wasn’t enough to save the system.

Source: eBay

With the 7800, they didn’t take the risk. “Plays Atari 2600 cartridges” was printed right on the front of the box. But by then, the company had already lost momentum. The effects of the 1983 crash were still unfolding, and Nintendo had moved in to take the lead. The 7800 did what the 5200 should have, but it came too late.

Sega Genesis adapter supports Master System

A built-in advantage that didn’t last

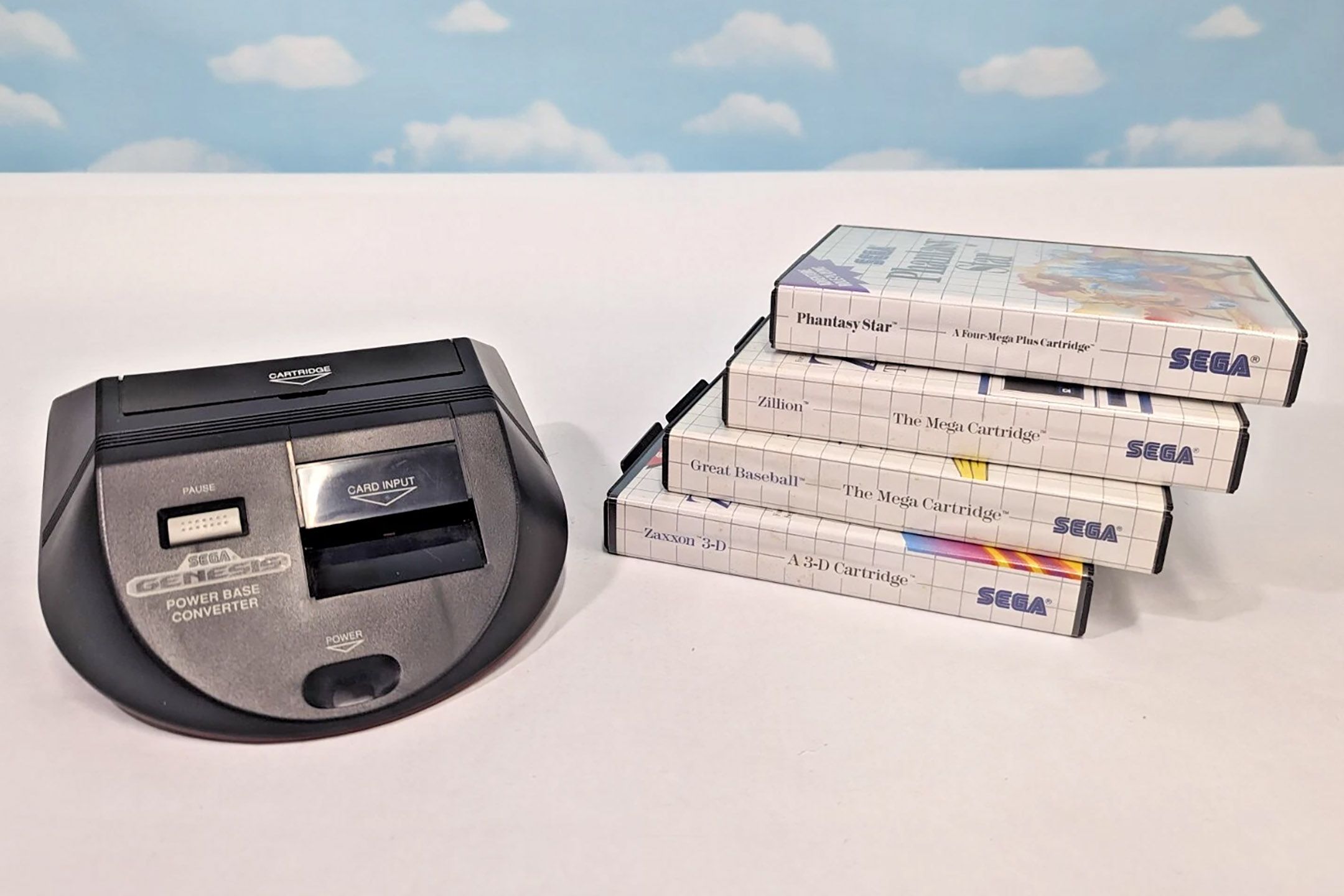

Source: eBay

Like the Atari 7800, the Sega Genesis carried over hardware from the previous generation. The Z80 processor and SN76489 sound chip—core components of the Master System—were already part of the Genesis design. They handled secondary tasks like audio, but their presence made backward compatibility possible. To take advantage of that, Sega released the Power Base Converter.

The adapter plugged into the Genesis cartridge slot and activated a different operating mode. The bus controller idled the Motorola 68000 processor, and control shifted to the Z80. The system’s video output stayed active, but it wasn’t a perfect match for older titles. Games from the SG-1000 didn’t work, and a handful of Master System games required the original controllers. By that point, Sega had already pulled them from retail—players had to request one directly from Sega.

Compatibility was still strong overall. In regions where the Master System had traction—especially Brazil and Europe—it gave players a simple way to keep playing their existing games. But Sega didn’t stick with it, and the Saturn dropped support, as did the Dreamcast. The Power Base Converter worked, but it was the last of Sega’s backwards compatibility—at least hardware-based.

Nintendo SNES drops support for NES

A clean break that didn’t sit well with everyone

Source: Benjamin Zeman

When Nintendo launched the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES) in 1990 (1991 in North America), it made a decisive break from the past. The new console introduced a different CPU architecture and a redesigned cartridge format, rendering it incompatible with the original NES library. Players had to keep their old consoles if they wanted to revisit classics like Super Mario Bros. or The Legend of Zelda.

This departure from backward compatibility was a notable shift, especially considering that during the SNES's initial unveiling to Japanese journalists on November 21, 1988, Nintendo showcased a prototype accessory called the "Famicom Adapter." This device was intended to allow the upcoming SNES to play Famicom (NES) games, providing a bridge between the two generations. However, this adapter never reached the market, and Nintendo proceeded without any official means to support NES titles on the SNES.

Related

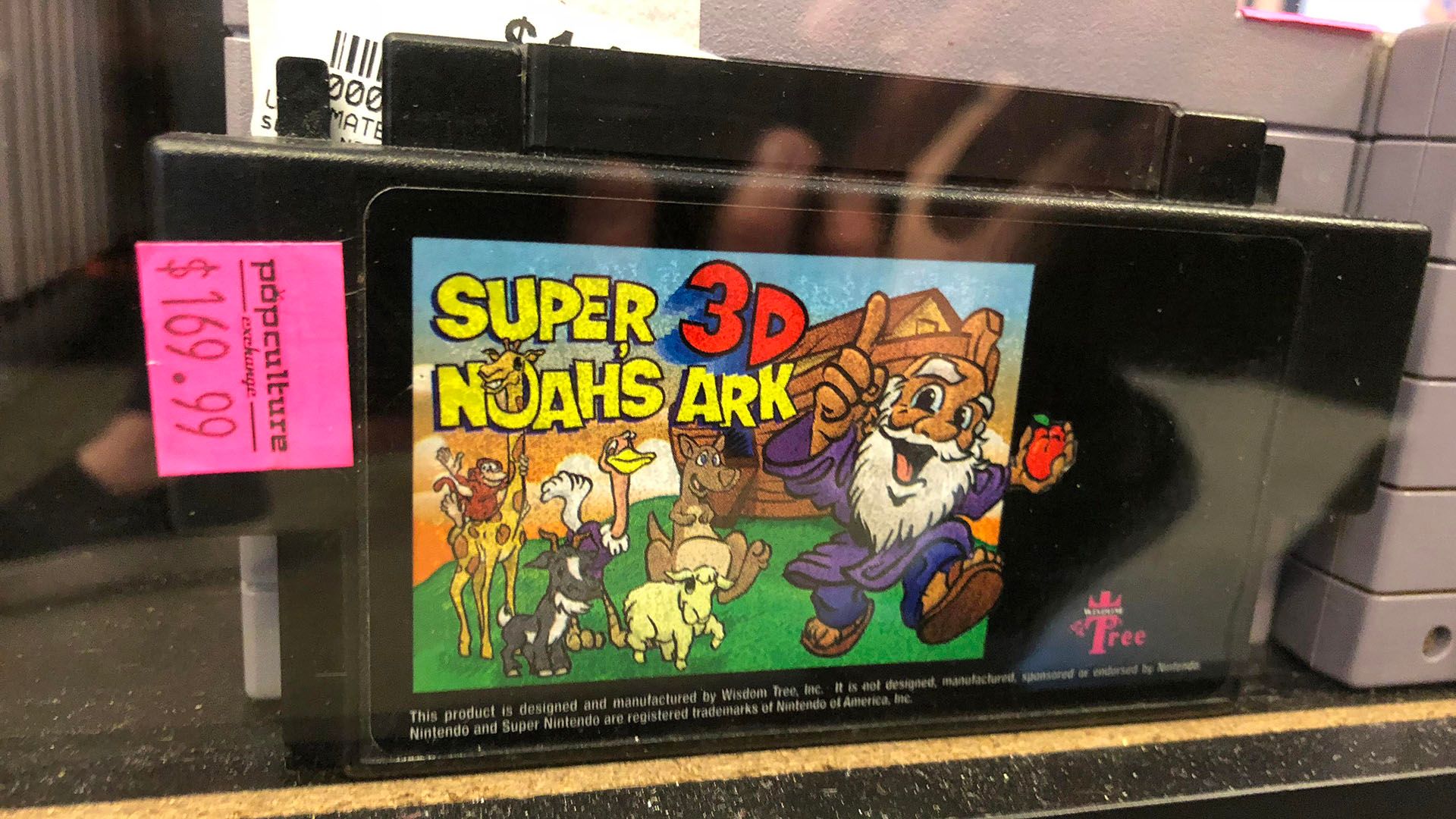

The only unlicensed SNES game ever commercially released

Super Noah’s Ark 3D’s release was perfectly timed—a first-person shooter where you didn’t shoot anyone.

Interestingly, remnants within the SNES hardware suggest that true backward compatibility was considered. Hardware expert Foone noted in 2019 that "SNES carts actually start up in 8-bit mode. They then have to tell the CPU to switch into 16-bit mode… It starts up in 8-bit mode because that’s the mode it has to be in to run NES code." This insight indicates that the SNES's design initially had provisions to accommodate NES software, but these features were ultimately left unused.

While the SNES moved forward without native support for NES games, Nintendo explored other avenues to bridge generational gaps. In 1994, they released the Super Game Boy, an adapter that allowed Game Boy cartridges to be played on the SNES, displaying handheld titles on a television screen. This innovation demonstrated Nintendo's recognition of the value in cross-generational play, even if it wasn't applied to their primary console lineage at that time.

Nintendo handhelds maintain compatibility

Game Boy, Color, and Advance keep the library intact

Source: Nintendo

While Nintendo’s home consoles broke with the past, its handhelds moved in the opposite direction. The Game Boy Color, released in 1998, ran nearly every original Game Boy game without modification. Nintendo followed that with the Game Boy Advance in 2001, which kept support not only for Game Boy Color titles but for the original black-and-white Game Boy library as well.

The Game Boy Color shared the same basic CPU as the original, and the Advance included the full hardware needed to run both older systems. Players didn’t need an adapter or software workaround—the cartridges just worked. For many, this backward support was the reason to upgrade. It meant trading up without starting over.

That continuity helped solidify Nintendo’s dominance in the handheld space. Players could carry entire collections forward, sometimes across more than a decade of hardware. It also showed that when compatibility was part of the design from the beginning, it could be seamless, reliable, and expected.

Nintendo revisits handheld games on home hardware

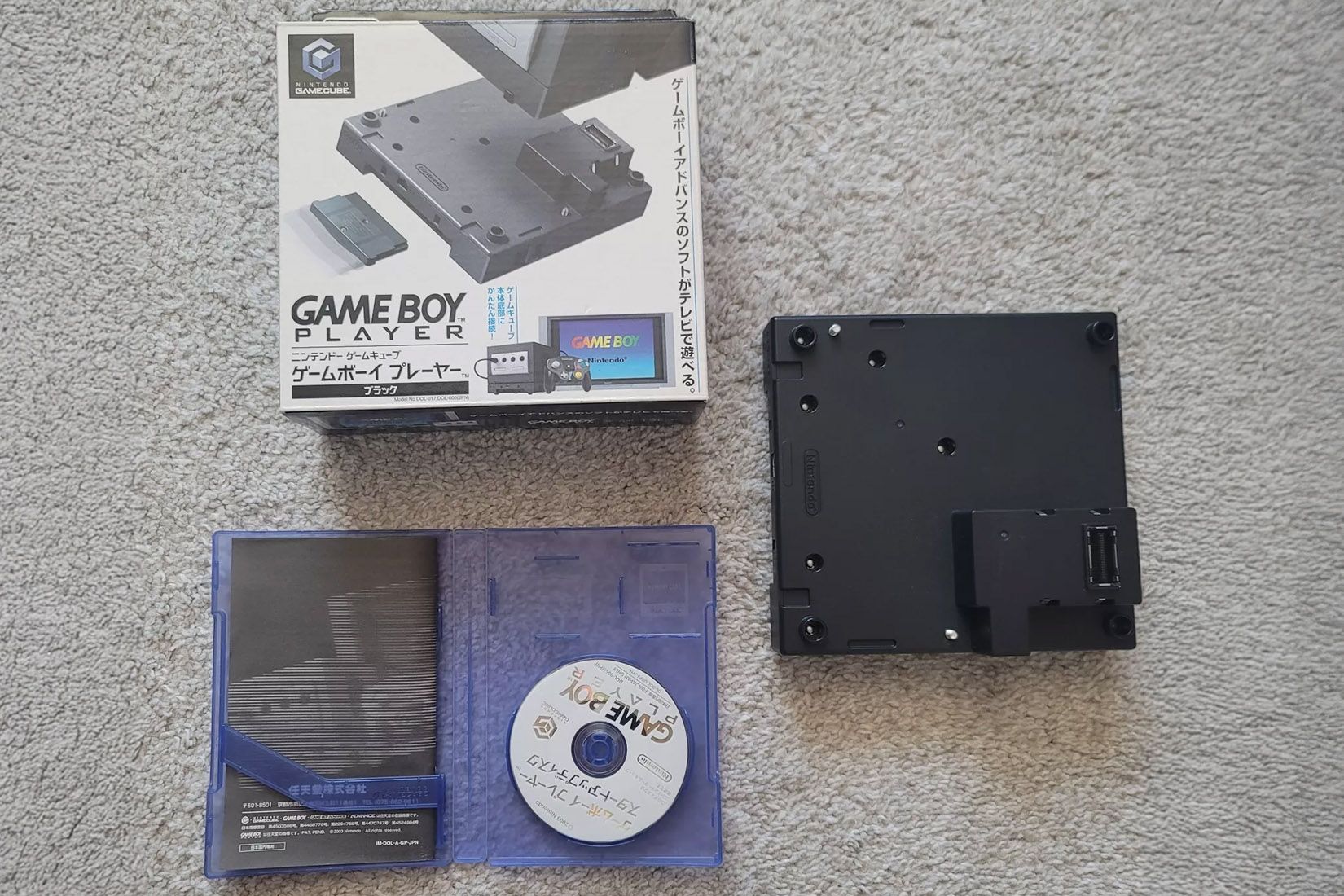

The Game Boy Player brings portable libraries to the TV

Source: eBay

In 2003, Nintendo released the Game Boy Player, a hardware accessory for the GameCube that let users play physical Game Boy, Game Boy Color, and Game Boy Advance cartridges on a television. The unit attached to the underside of the console and used native hardware—not emulation—to run the games. A boot disc launched the software interface, but the cartridges themselves loaded directly from the attached reader.

Unlike the Super Game Boy on the SNES, which only supported original Game Boy titles and added limited enhancements, the Game Boy Player covered three generations of portable games and maintained near-complete compatibility. It didn’t upscale graphics or add features, but it gave players a straightforward way to keep using their existing cartridges without switching platforms.

The lost generation of compatibility

Sega, Nintendo, and the rise of emulation

Source: eBay

In the mid-1990s, backward compatibility hit a wall. The Sega Saturn, released in 1994, introduced new hardware and media formats that made support for the Genesis or Master System impossible. There was no adapter, no fallback, and no plan to carry older libraries forward. The Dreamcast followed in 1998 with a similar break—strong launch titles, online play, and zero compatibility with previous Sega systems.

Nintendo took the same approach. The Nintendo 64, launched in 1996, used a new cartridge format and controller layout. No NES or SNES titles were supported, and no official effort was made to keep older games accessible. For a while, backward compatibility simply vanished from home consoles. But outside that ecosystem, things were shifting.

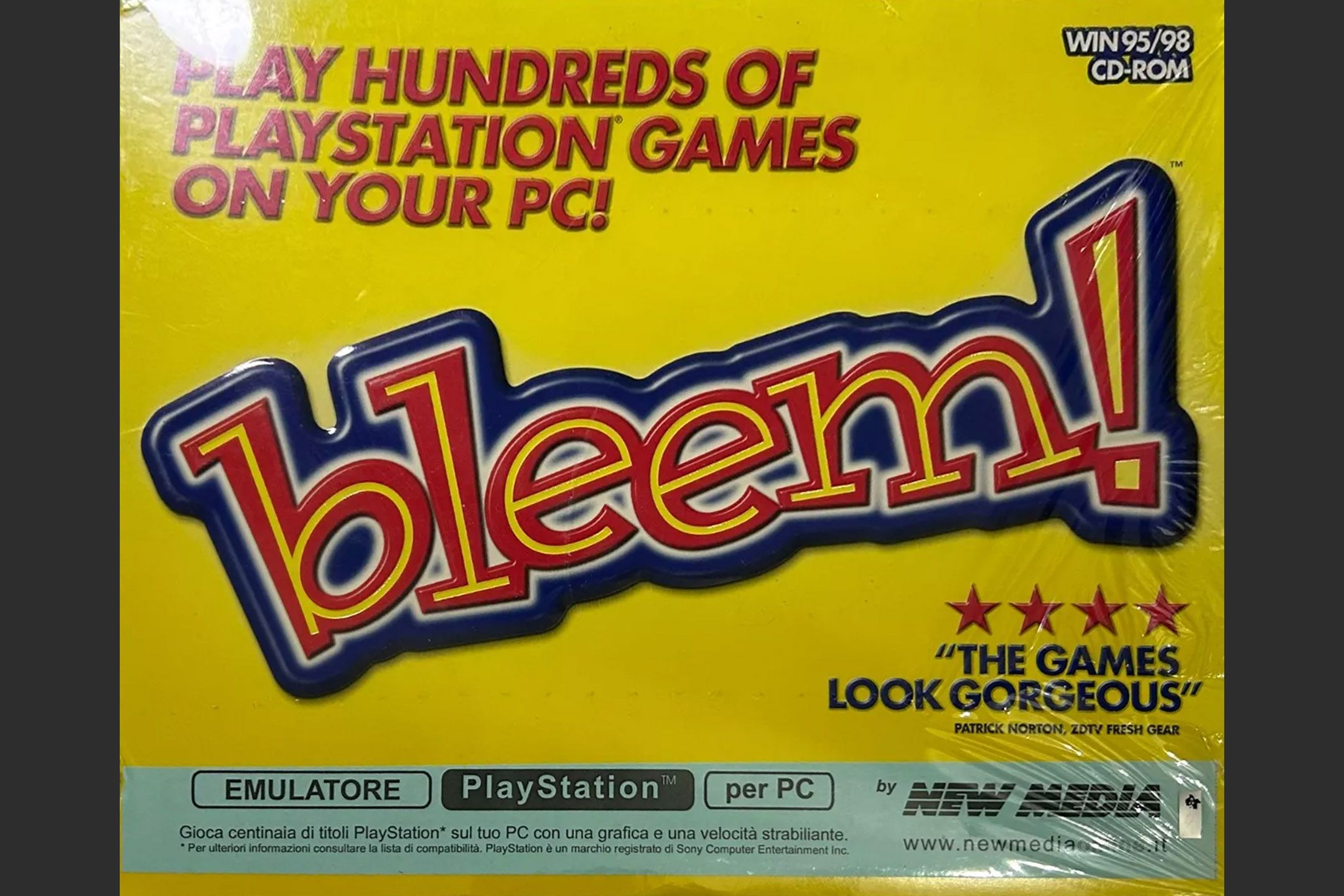

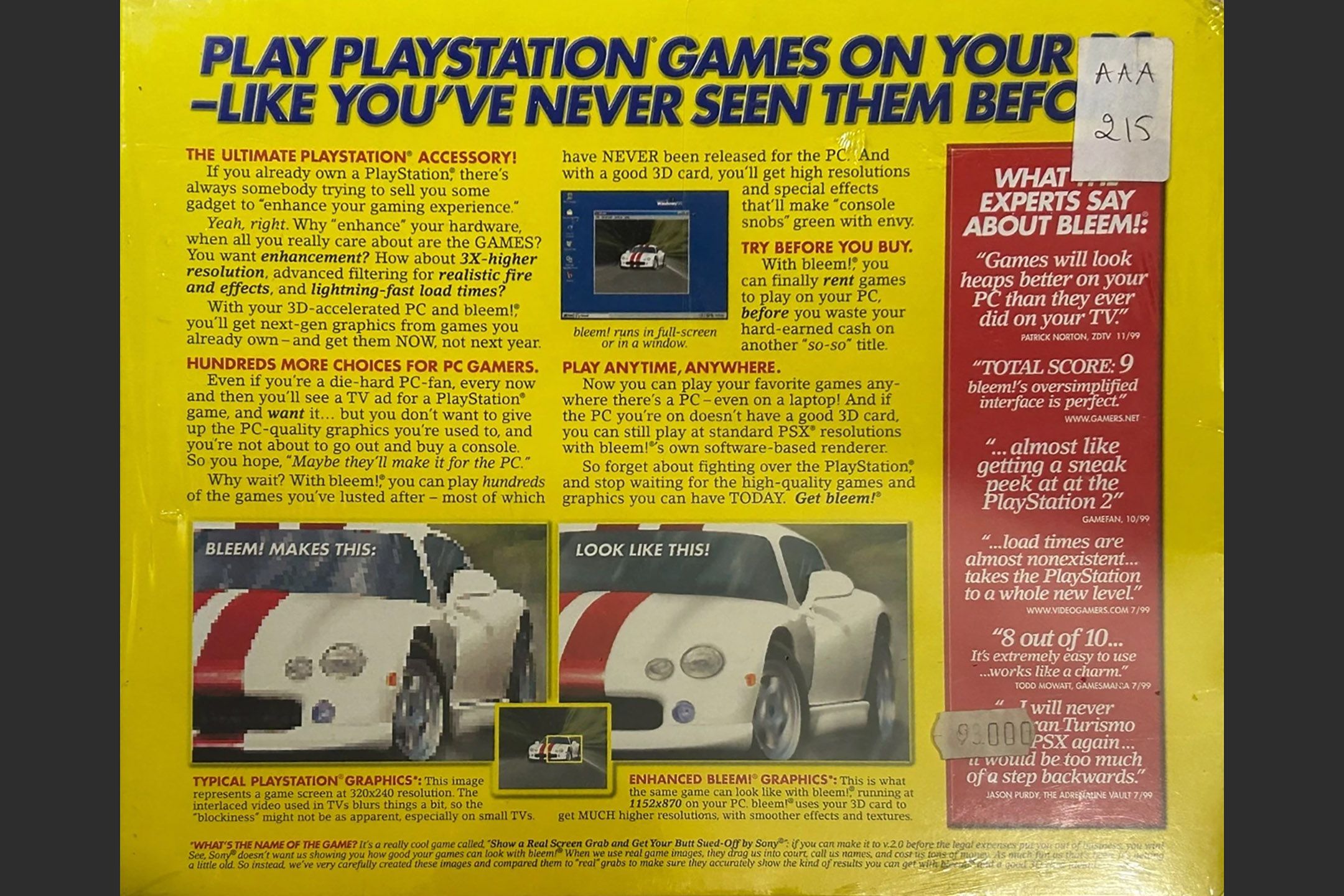

PCs were getting powerful enough to emulate older hardware, and classic arcade cabinets and consoles became targets. By 1999, bleem!—a commercial PlayStation emulator—was being sold at retail.

Source: eBay

Even the Dreamcast, which lacked support for Sega’s own back catalog, ended up running emulators. A version of bleem! was released for the system, allowing a handful of PlayStation games to run on Sega hardware. Developers quickly took interest. The Dreamcast’s open architecture made it a popular platform for homebrew emulators. Near the end of its life, Sega released a Genesis emulator for the Dreamcast. Around the same time, Nintendo created internal emulators for NES and N64 titles on the GameCube.

Source: eBay

Sony PlayStation 2 supports original PlayStation

Hardware-level compatibility drives early adoption

Source: eBay

When Sony launched the PlayStation 2 in 2000, it came with full support for the original PlayStation library. The console included the same R3000A processor used in the PS1—now repurposed as an I/O controller—which allowed it to run nearly all PS1 games natively. It also supported original memory cards and controllers, making the transition between generations almost frictionless.

This wasn’t just a bonus. The PS2 had a limited launch lineup, and backward compatibility gave early buyers something to play on day one. Combined with its ability to double as a DVD player, the PS2 became one of the most popular pieces of consumer tech at the time—a game console and media player in a single unit.

It worked. The PS2 went on to sell over 155 million units, becoming the best-selling home console of all time as well. Compatibility wasn’t the only reason—but it gave Sony an edge, and it set a new bar for what players would expect from future hardware.

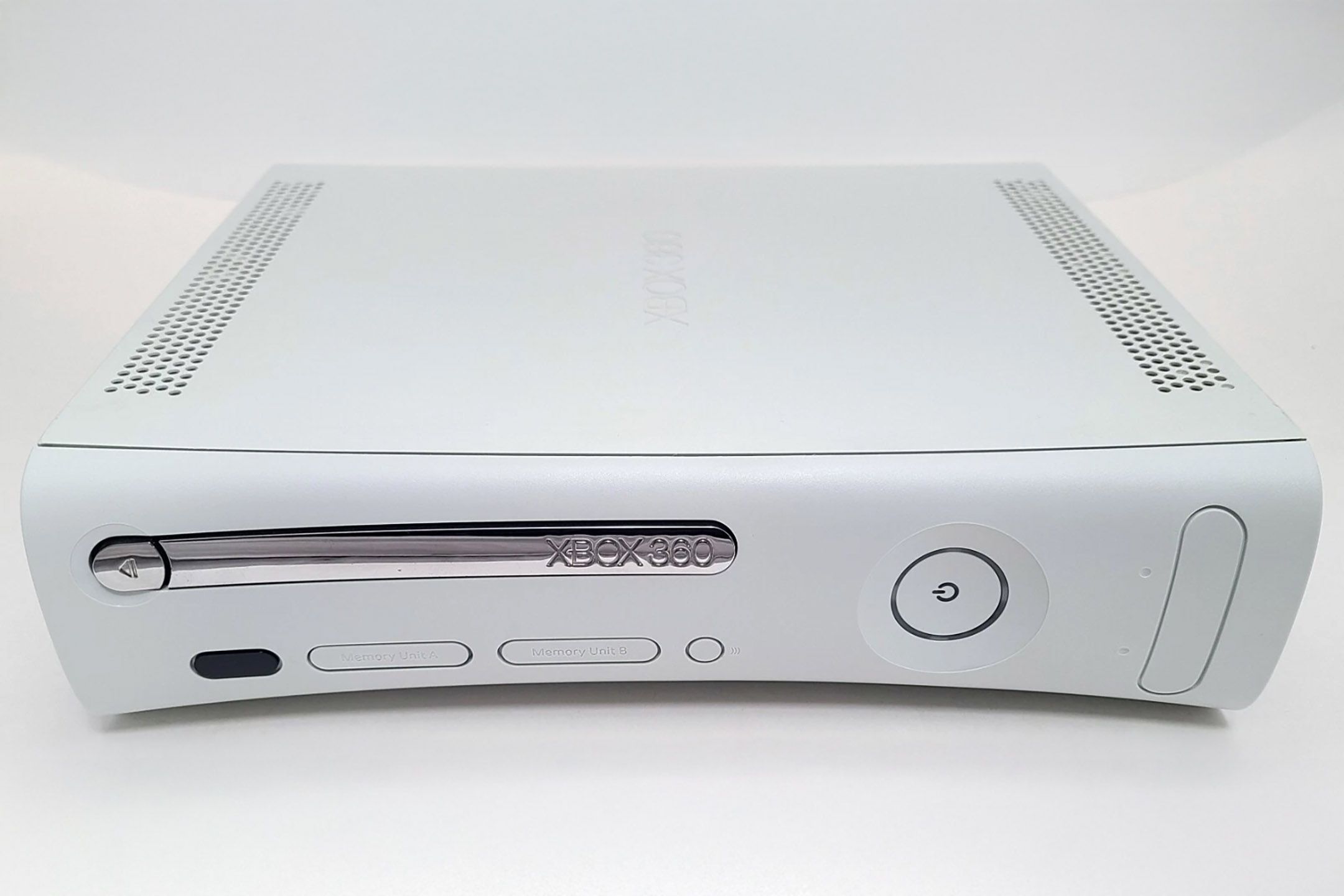

Microsoft Xbox 360 introduces emulation

Software-based support replaces legacy hardware

Source: eBay

When Microsoft launched the Xbox 360 in 2005, it didn’t include native support for original Xbox games. The hardware was entirely different—PowerPC architecture instead of x86—and the components that made the original Xbox tick weren’t present. But this time, compatibility mattered. Players had built libraries, and Microsoft needed a solution.

They turned to software. Instead of including Xbox hardware in the 360, Microsoft developed individual emulation profiles for each supported game. These patches translated the original code to run on the new system, with mixed results. Some games ran well. Others had audio glitches, visual errors, or performance issues. Compatibility depended on whether Microsoft had created and tested a profile for that title.

At launch, only a small fraction of the Xbox library worked, but Microsoft expanded the list steadily based on demand. Players could load supported games from their original discs or download them digitally if available. It wasn’t seamless, and it wasn’t complete—but it was the first time a console maker tried to retrofit backward compatibility entirely through software.

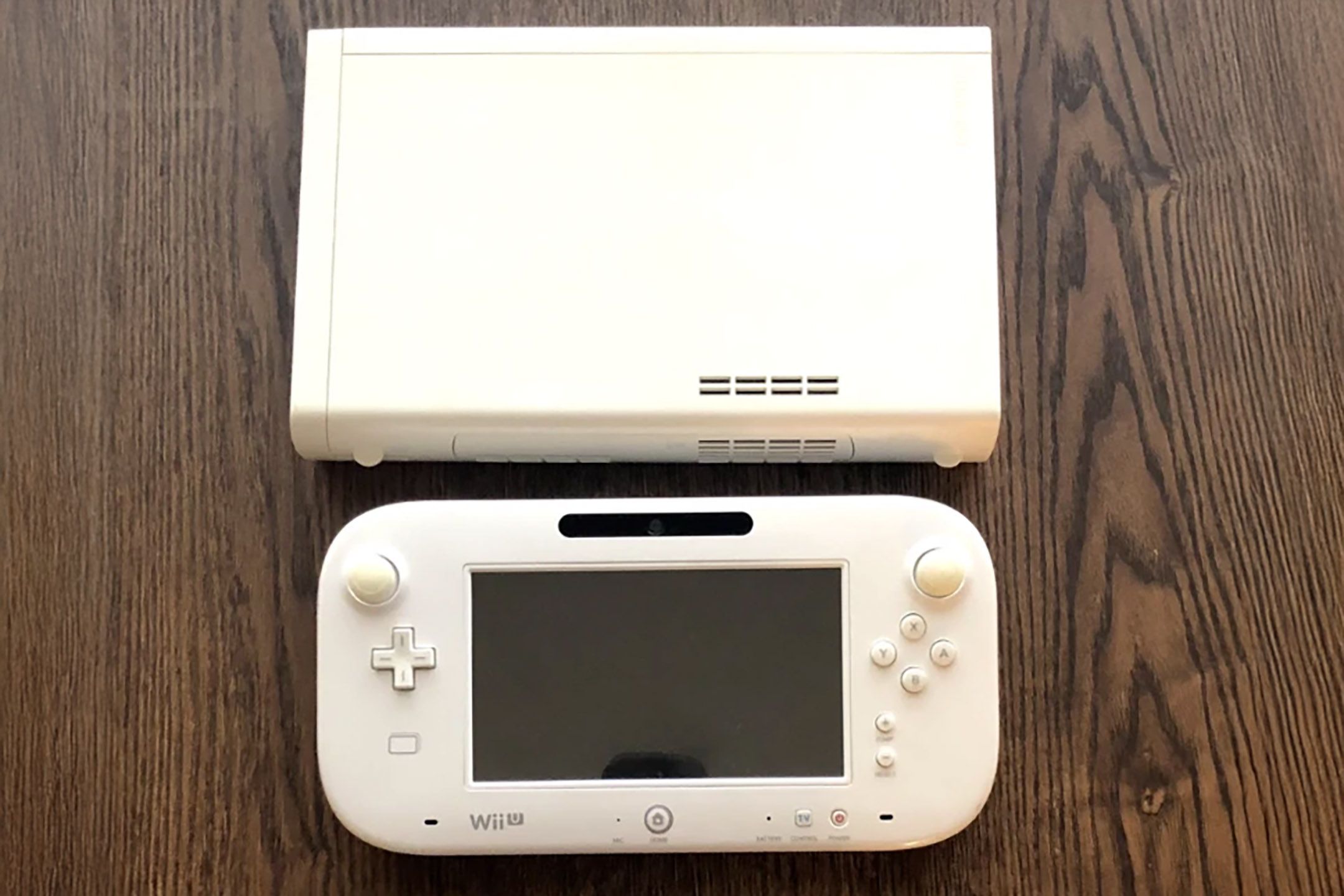

Nintendo Wii and Wii U maintain limited hardware support

One generation forward, nothing beyond

Source: eBay

When Nintendo released the Wii in 2006, it marked the company’s return to backward compatibility on home consoles. The Wii was fully compatible with GameCube discs, memory cards, and controllers. Users could insert a GameCube disc, plug in original controllers, and play without adapters or patches.

The Wii U followed in 2012 with a similar approach. It supported nearly all Wii games and accessories, including Wii Remotes and the sensor bar. But GameCube support was removed entirely. Discs no longer worked, memory cards couldn’t be used, and the controller ports were gone.

The rest of Nintendo’s legacy libraries weren’t supported at all through hardware. There was no way to play SNES, N64, or Game Boy cartridges on the Wii or Wii U. Instead, Nintendo offered a limited selection of older games as digital downloads through its Virtual Console service. It wasn’t true backward compatibility—just a storefront with re-releases that ran in Nintendo's own proprietary emulation software.

Sony’s shifting stance on compatibility

PS3, PS4, and PS5 show three different approaches

Source: PlayStation

Sony followed the success of the PlayStation 2 with the PlayStation 3 in 2006—but its approach to backward compatibility didn’t stay consistent. Early PS3 models included the actual hardware from the PS2: both the Emotion Engine CPU and Graphics Synthesizer GPU were built into the launch systems, allowing nearly perfect compatibility with PS2 discs. But the added cost became a liability. By 2007, Sony began removing those components from newer models to lower the retail price. Software-based compatibility was limited, and many PS2 games stopped working entirely.

By the time the PlayStation 4 launched in 2013, Sony had dropped physical backward compatibility altogether. PS3, PS2, and original PlayStation discs weren’t supported, and no legacy hardware was included. Instead, Sony offered a separate streaming service—PlayStation Now—that let users play a curated list of older titles via the cloud. The experience varied depending on connection quality, and none of it worked with players’ existing game discs.

The PlayStation 5 brought compatibility back, but only for PS4. It supported over 99% of the PS4 library, with most titles running natively and benefiting from faster load times and improved performance. Sony had moved from full hardware support to streaming, through its PlayStation Plus subscription.

Microsoft adopts software-based emulation

Xbox One and Series X/S go all in

When Microsoft launched the Xbox One in 2013, it didn’t include any support for older games. The company had changed hardware architectures again, and compatibility with Xbox 360 discs was initially off the table. But in 2015, that changed. Microsoft introduced software-based emulation for select Xbox 360 titles, and unlike the Xbox 360’s original approach, this time it worked better. Players could insert supported discs, download a digital version, and run the game with improvements like faster load times and stable frame rates.

Over time, Microsoft expanded the list to include original Xbox games as well. The company built a unified emulation layer that allowed older titles to run across Xbox One and later, the Series X and S. Backward compatibility wasn’t universal, but it was deep—and in many cases, enhanced. Some titles ran at higher resolutions or doubled frame rates compared to their original releases.

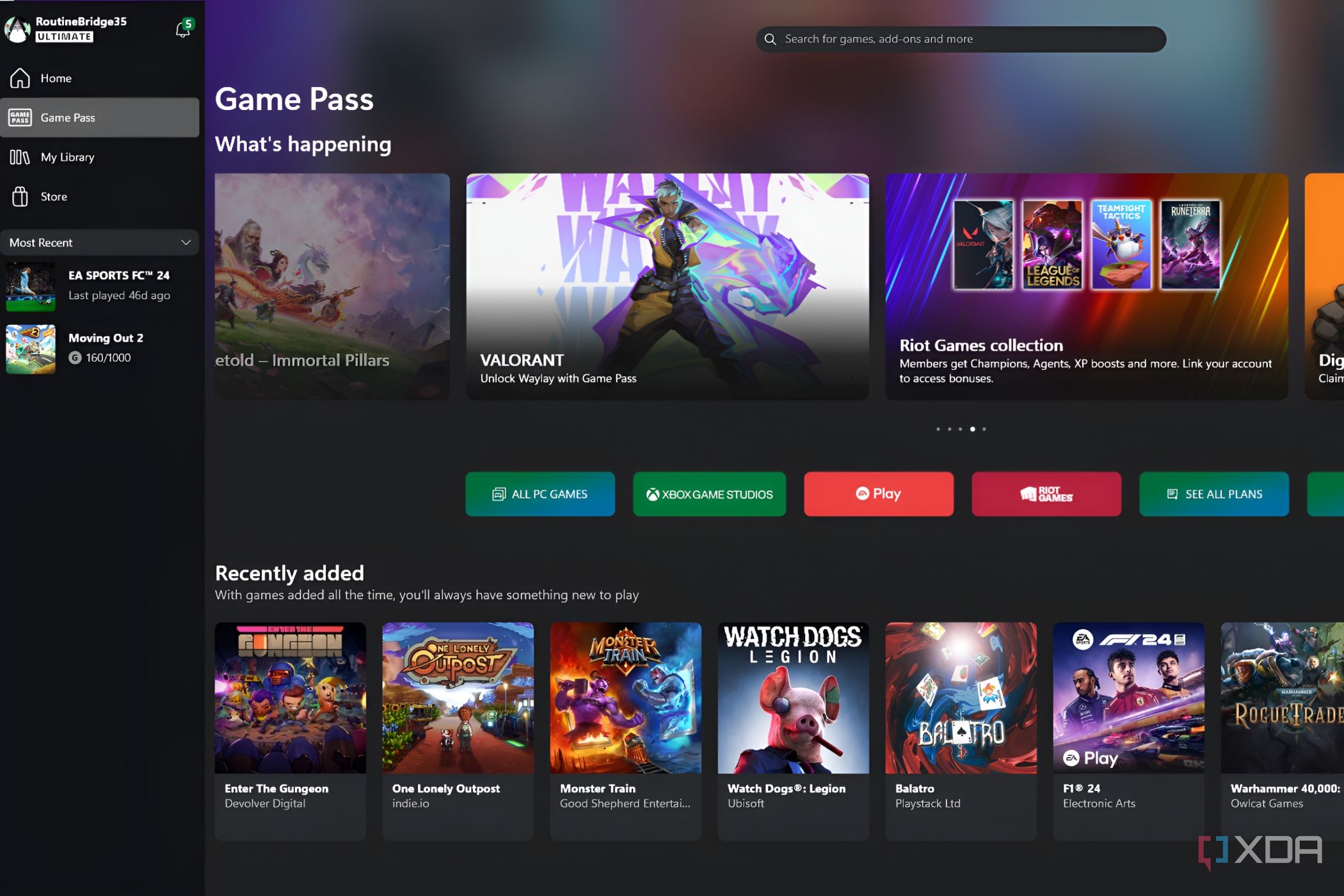

Microsoft also integrated this strategy into Game Pass. Legacy games weren’t just playable—they were accessible as part of a subscription, with save syncing, achievements, and cross-generational play. While Sony and Nintendo limited support to select platforms or premium services, Microsoft treated compatibility as a long-term feature, not a marketing cycle.

Nintendo Switch breaks the chain

No legacy support, no physical options

When the Nintendo Switch launched in 2017, it dropped backward compatibility in all forms of hardware. But Nintendo didn’t bring back the Virtual Console. Instead, it introduced a subscription service—Nintendo Switch Online—that offered a small, curated list of emulated NES and SNES games. N64, Game Boy, and Game Boy Advance libraries were added later through an expansion tier. Players paid a recurring fee for limited access to a rotating selection of titles, with no option to buy them outright and no support for the games they already owned.

That gap didn’t go unnoticed. Plenty of emulators, like Snes9x, Dolphin, and ZSNES already existed for older Nintendo games, and community-built emulators like Ryujinx and Yuzu emerged for the Switch itself. Like in Brazil during the 1980s and ’90s, when official distribution failed, the audience found its own way. The Switch era repeated that pattern in a new form.

In 2024, Nintendo responded with lawsuits. Yuzu was shut down after a $2.4 million settlement, and Ryujinx went dark shortly after—but multiple forks rose up in their place. Nintendo wasn’t just stepping away from physical support—it was actively shutting down the tools players were using to access games the company no longer offered.

Related

Console meets cartridge: Breaking down the architecture of the NES’s unique design

The NES architecture can be divided into three key groups: CPU-related components, PPU-related components, and cartridge-specific components

What stays and what gets left behind

Backward compatibility has rarely been about technical limits. It’s always been a choice—sometimes made early, sometimes made under pressure, and sometimes not made at all. Atari figured it out in 1986. Microsoft turned it into a platform feature. Nintendo dropped it entirely with the Switch, then sued the people filling the gap.

Players have carried libraries across decades. Companies haven’t. From cartridge slots to subscription models, support has been inconsistent at best and disposable at worst. When access disappears, emulators take over. They do the job console makers won’t. Not perfectly, not always legally, but with more care than the companies that built the games in the first place.

The next generation of hardware is already on the way. Backward compatibility won’t just be expected, it will be demanded, but it's not that hard when everything's gone digital anyway. And if it’s not there, people will find it somewhere else.

.png)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·