Innovation keeps racing forward, yet a growing number of people are deliberately stepping back—especially as a constant onslaught of unwanted AI from every angle is being used as a corporate excuse to raise subscription prices for software we can't even own. They're trying to make it so nothing is ours anymore; everything is rented to us, from video games and SaaS to movies and books. Even hardware faces planned obsolescence, forced upgrades, and a long fight for the right to repair.

Retro gear offers an alternative—a chance to make something ours again. From old game systems to vinyl LPs, retro hardware and media have slipped into daily life rather than staying on collectors’ shelves. But retro gear isn't just for nostalgia—it's a platform for creativity.

We love finding new uses for old tech, from repurposing hard drives to building media servers out of old parts. Old tech is familiar and easier to understand, which means it's easier to hack, mod, and find new uses for—even things it was never intended to do. This isn’t mere nostalgia; it’s a conscious re-evaluation of what technology should do and how it should feel in an always-online age.

Simplicity makes old tech flexible

We figured it out together

When old video game systems or computers first came out, they were cutting edge—and much of their design, including how they worked, was proprietary. But over time, schematics leaked, patents expired, and curious hobbyists reverse-engineered what once seemed like black boxes. As general knowledge about circuits and components grew, so did our ability to understand and modify these machines.

Replacing capacitors in a Commodore 64, modding a retro system for composite or HDMI output, or writing a simple BASIC game offers a clear and tangible learning curve. The barrier to entry is low: parts are cheap, documentation is widely available, and communities are eager to help newcomers get started.

That approachability has turned repair and restoration into a genre of its own. YouTube channels like The 8-Bit Guy have topped one million subscribers by diving deep into rare and bizarre media formats I’d never even heard of. It was YouTuber Ben Heck who got one of the rarest consoles of all time—the Nintendo PlayStation prototype—working again. And creators like Sayaka’s Digital Attic offer a peaceful glimpse into what it’s like for hobbyists like me, who just do this for fun.

My workbench is one of the places I go to relax. Unfortunately, I won’t have access to it for a few months—so for now, I’m living vicariously.

Retro technology seems infinite

Each discovery holds creative potential

Humans have built a staggering amount of technology over the last century, and so much of it remains hidden in history. There’s always another obscure machine to stumble across—one more artifact waiting to be understood.

Take the Bendix G-15, a computer from 1956 that used vacuum tubes for both logic and memory. It’s considered by some to be the oldest running digital computer in North America—at least, publicly known. Weighing in at about a ton, the G-15 was recently restored by YouTuber Usagi Electric. It featured a drum memory of 2,160 29-bit words, plus 20 additional words for special functions and rapid-access storage.

Related

Unmasking the Dead Internet: How bots and propaganda hijacked online discourse

You’re not imagining it. The internet feels fake because most of it is—automated, scripted, and engineered to distort what’s real.

The base unit cost $49,500 at the time, but a working configuration typically ran closer to $60,000—over $700,000 when adjusted for inflation. Alternatively, it could be rented for $1,485 a month (about $17,460 today). It was never meant for consumers; it was designed for scientific and industrial use.

If a machine like this were built today, most of us would never see it—just as we didn’t back then. It was too specialized, too expensive, and too far removed from everyday life. And yet, through restoration efforts and online platforms, we now have the chance to witness these rare systems in action. People like Usagi Electric don’t just bring the hardware back—they bring the history with it, giving us a window into how these early machines worked, how they were built, and why they mattered. It’s not just preservation—it’s education.

Modern Tech has advanced beyond individual access

But we can recreate the past ourselves

Modern cutting-edge tech, like Microsoft’s Majorana 1—the world’s first quantum chip powered by topological core architecture—is nearly impossible to grasp unless you’re already deep in the field. Even the microchips inside our everyday phones and laptops are layered with so much complexity that understanding or replicating them requires specialized tools, clean rooms, and massive industrial infrastructure. That’s also why it’s unrealistic to think we can simply bring all of this manufacturing back to the U.S. overnight.

Recent efforts—like President Trump’s tariff-driven policies aimed at reviving domestic hardware production—are unlikely to yield meaningful results within a single term. The U.S. economy has already evolved away from manufacturing, shifting its focus toward SaaS, cloud infrastructure, and information technology. Trying to force a reversal at scale is not only economically regressive, but strategically out of step with the industry’s trajectory.

But if reclaiming control over modern tech is out of reach, reclaiming older tech is not—and, ironically, it’s our shift toward information systems that made this possible. The rise of open-source platforms, online communities, and decades of shared documentation has created a vast knowledge base that hobbyists can tap into. We've had time to study retro systems, and much of it can now be understood, modified, or rebuilt by individuals.

While it’s not feasible to fabricate our own integrated circuits, we can design custom PCBs, 3D print enclosures for our projects, or even build functioning 4-bit computers out of nothing but transistors, resistors, and other discrete components. What once required teams of engineers and expensive labs can now come together on a soldering mat in someone’s garage.

That accessibility is empowering. We don’t just get to own these machines—we can master them. We can take them apart, rebuild them, and reshape them to suit our curiosity and creativity. In an era of sealed devices and abstracted systems, building retro hardware by hand is a reminder that real technical agency is still within reach.

And that’s what makes the Trump administration’s approach so hollow. It clings to a fantasy of an industrial revival while ignoring the reality of where progress is actually happening. The industrial age is over in the U.S.—we led the charge into it, and then led the world out of it. Since then, we’ve not only lived through the information age, we’ve helped pioneer the era of AI and automation. We're not one step ahead—we're two ages beyond. This policy doesn’t just miss the point; it reads like the wishful thinking of someone too out of touch to see the world as it is.

A digital generation turns to analog comfort

A break from algorithmic overload

A new generation has grown up entirely in the post-industrial world—raised on the internet, shaped by algorithms, and fluent in digital systems. They’ve developed a different set of skills, expectations, and ways of thinking. But while their digital fluency could be harnessed to build the future, they’re rarely given the space or tools to do it. Instead, they’re trapped in ecosystems designed to extract attention, data, and labor—systems that exploit them while actively denying them compensation, agency, or ownership.

And they know it. They're fully aware that their time and creativity are being harvested, commodified, and sold—without their permission and without a paycheck. The systems meant to connect and empower are instead draining them, locking them into roles as consumers and content rather than creators. So where else can they turn?

If the platforms of the present are designed to hold them back, many are choosing to look to the past. Old tech offers an escape route—one not controlled by metrics or monetization.

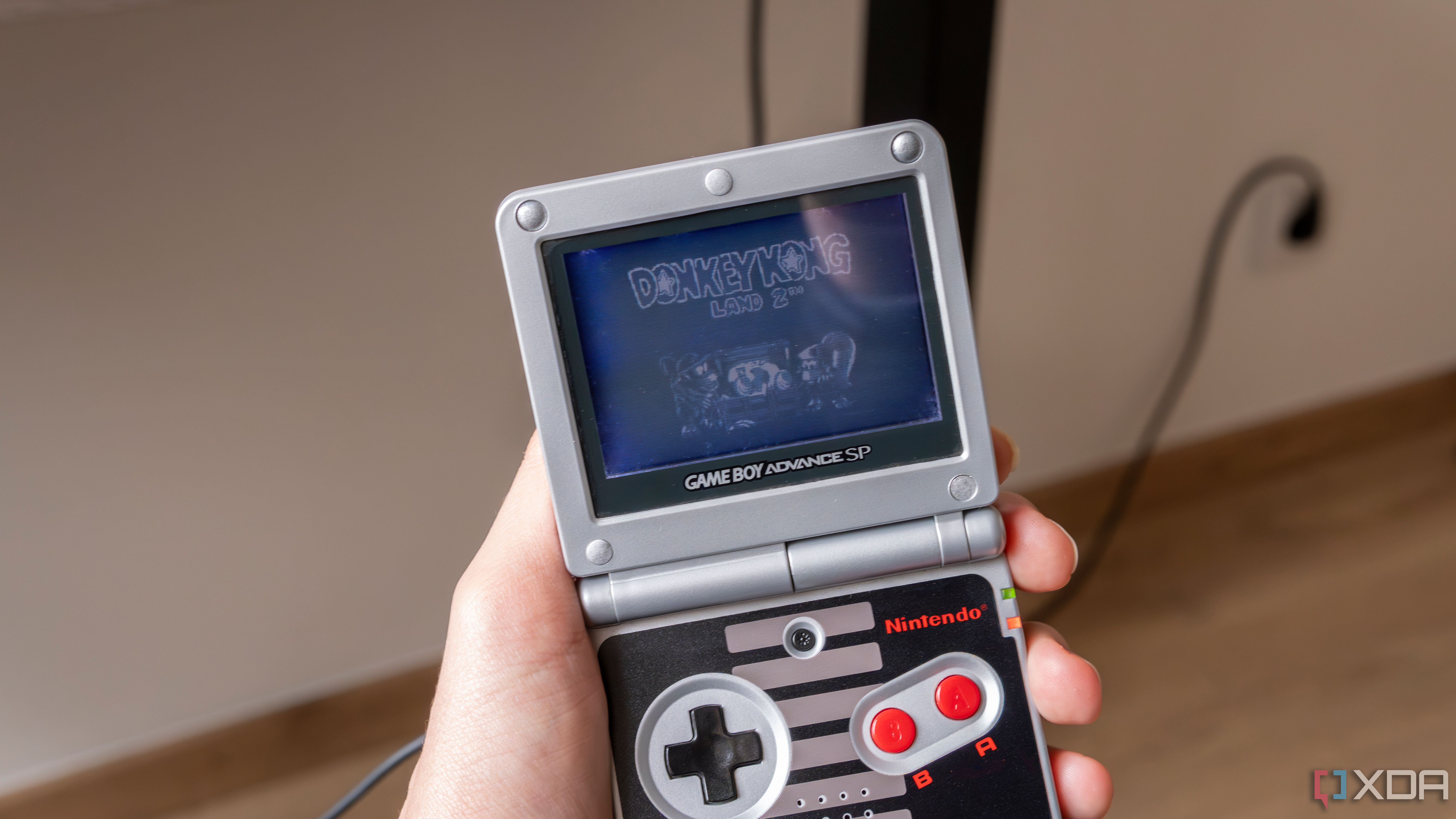

Older hardware also delivers a psychological detour—no-stress play sessions with no bloatware, no patches, and no push notifications competing for attention. Nothing updates in the background, nothing asks for personal data, and nothing yanks players toward in-app purchases. What you have in front of you is what you get to play with.

That kind of digital minimalism can feel ritualistic. It grants a reprieve from always being sold something, told what to think, and pushed to constantly check your notifications. It's not about rejecting progress—it's about reclaiming presence.

Old aesthetics as a foundation for new creation

When access to the future is cut off, people turn to what’s still open. And for a generation raised in closed systems, that often means going backward. Not because the past is better, but because it’s still within reach. The urge to create never goes away—it just finds whatever tools are available.

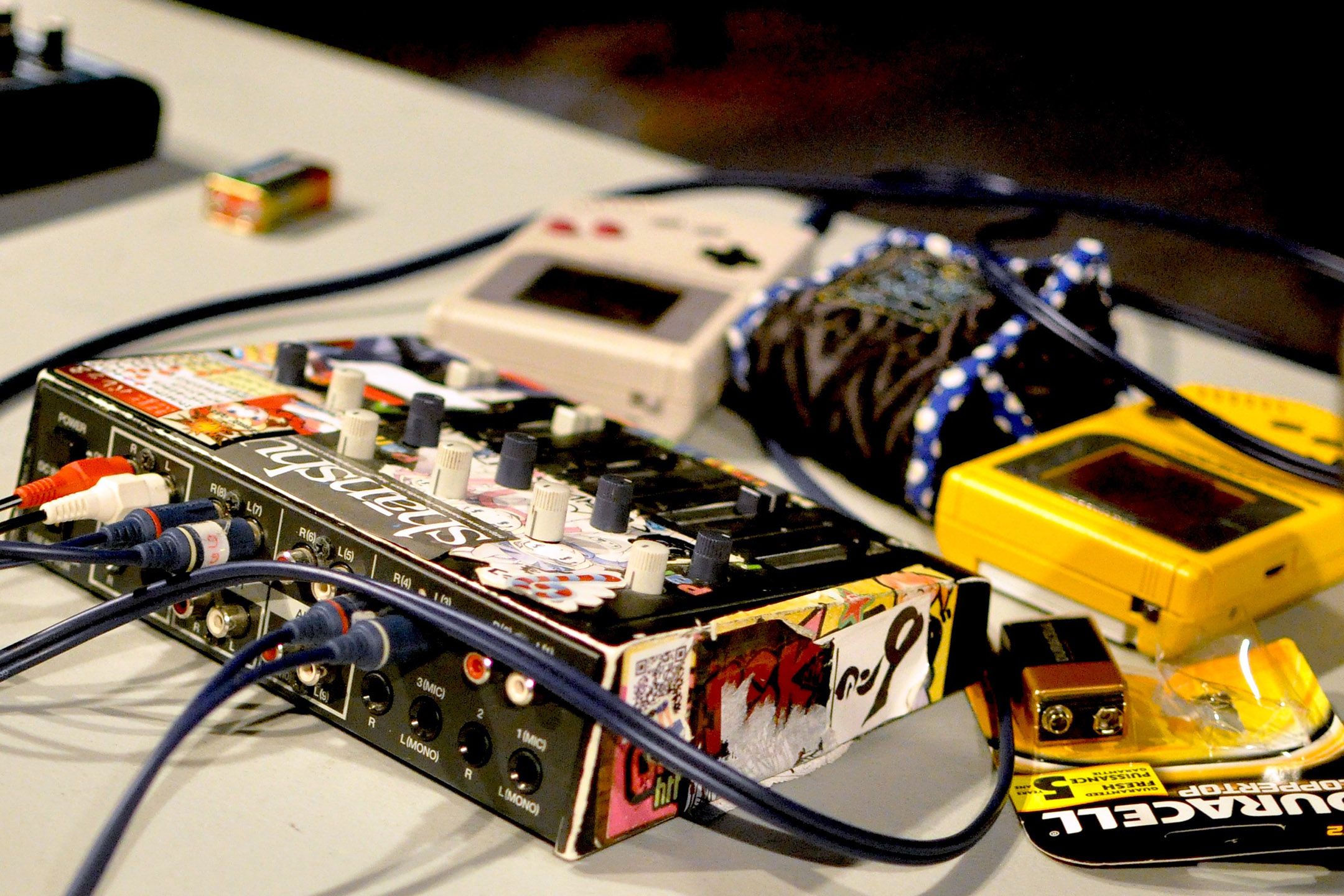

So they build with what they can: pixel art, chiptunes, zines, and emulated hardware. They make games like Shovel Knight and Celeste—titles that borrow the look and limitations of 8-bit systems, but push gameplay and mechanics in entirely new directions. They work inside these old boxes—256-color palettes, four or five sound channels, rigid screen resolutions—and produce work that feels precise and intentional.

Source: Wikipedia - Lucius Kwok

Constraints don’t stifle creativity—they sharpen it. When the boundaries are known, you can focus. There’s no guesswork, no feature creep, no updates to chase. Just a limited set of tools and a clear canvas. These styles have endured not because they’re simple, but because their limits are transparent, and working within them demands real choices.

Until the future opens up, this is where people are making things—inside the boxes they understand.

Making use of what we already have

A response to throwaway culture

E-waste now exceeds 60 million metric tons a year, and a growing number of hobbyists treat retro builds as an answer to that problem. Salvaging old parts, repairing outdated systems, and finding second lives for forgotten hardware isn’t just practical—it’s a quiet resistance to disposable design.

Plenty of us have a desktop graveyard tucked away somewhere. Boxes of cables. Stacks of old hard drives. CPUs and GPUs from five, ten, fifteen years ago. I’ve personally salvaged and sold hundreds of sticks of RAM from nearly every generation, along with dozens of processors and PCIe cards. And the demand is still there.

I often wonder what someone is buying that old SDRAM for—what will my old project’s parts end up doing in the future?

Retro tech has become an endlessly hackable resource pool. I learned to solder by taking apart junk electronics. I learned how to fix computers by building them from whatever I could find. And if you’re here, there’s a good chance you did too.

Why retro comes back around

Maybe retro’s resurgence is more than nostalgia—it’s a quiet form of resistance. Planned obsolescence, subscription models, cloud dependency, and the loss of ownership have created a landscape where choosing tech that is finite, local, and fixable feels like a protest. Using old hardware becomes a way to push back, to opt out of being constantly upgraded and endlessly monetized.

In that sense, retro tech sits alongside other slow movements—like slow fashion, DIY repair, or farm-to-table eating. These aren’t just aesthetic choices. They’re cultural ones. They trade convenience for connection, efficiency for intimacy.

But vintage culture doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It’s fueled by modern infrastructure. Platforms like eBay and Etsy turn what used to be rare flea market finds into global resources. FPGA consoles like the Analogue Pocket reimagine classic formats with modern precision. YouTube tutorials tear down gatekeeping. And 3D printing makes parts for things no one manufactures anymore.

Culture doesn’t just loop—it re-emerges with context. And today’s context is defined by closed systems, passive consumption, and disconnection from how things actually work. Retro is a return to contact.

Related

From busted circuits to custom builds: Embracing the solder-first mindset

Turn broken electronics into hands-on lessons. Master soldering while embracing the DIY mindset of learning by doing.

Looking forward by looking back

Old tech still has something to teach us

Retro computing shows that progress isn’t a straight line—it moves like a helix. Always forward, but always rotating past earlier ideas from a different angle. In the right moment, the past lines up with what we need in the present, and becomes part of the path again.

Simplicity, self-repair, and sensory character are values that never vanished—they were just sidelined by economies of scale. And as complexity accelerates again through AI and abstraction, expect more people to seek out old tech in search of control they can actually grasp.

At the same time, AI is starting to reshape what’s possible. Tools that once required entire teams are becoming accessible to individuals. That shift could finally open the future for a generation that’s been boxed out. We’ll still be dealing with corporate control and tightly held platforms, but now the tools to push against them are starting to show up.

Retro tech gives us something to anchor to. It’s a stable point to tie a line around while we explore what’s coming next. It offers the knowledge we need to understand what we’re walking into, and a place to rest while the systems ahead continue to unfold. The renaissance of retro tech reminds us that innovation and reflection can move in tandem—and that sometimes the quickest way to the future is through learning about the past.

.png)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·